Zadzwoniłem do dobrze mi znanych drzwi i pomyślałem w tym momencie, że wszystko właściwie jest tak, jak kilka lat temu, kiedy szedłem się tutaj oświadczać. Butelka dla teścia, kwiaty dla teściowej, czekoladki dla szwagierki. Przyjęli mnie serdecznie. Jak wtedy.

– Co tam u Celiny? – zapytali.

– Jest w szpitalu. Lekarz mówi, że wszystko w porządku. Lada dzień będzie rodzić.

I tak się zaczęła rozmowa, podobna do tylu innych, prowadzonych w domach, gdzie wkrótce ma się pojawić potomek. Moja sprawa była jednak bardziej skomplikowana.

– W związku z tym wszystkim – zacząłem – mam do was, kochani, prośbę. Wkrótce mam możliwość wyjazdu. Myślę konkretnie o tym, żebyście mnie w rozmowie z Celiną poparli.

Nie będę mógł pomóc żonie w najtrudniejszych pierwszych tygodniach macierzyństwa, nie będzie mnie po raz pierwszy w domu w czasie Świąt Bożego Narodzenia, które zawsze są tak bardzo rodzinne, nasze. Do tej pory starałem się przestrzegać pewnej reguły: jedna wyprawa na rok. Ale wszystko zależy od nich, od tego, co powiedzą:

– Jeżeli to jest dla ciebie rzeczywiście takie ważne, to jedź. Pogadamy z Celiną... – powiedzieli.

Od tej pory, ilekroć słyszę płytkie dowcipy o teściowych, krzywię się z niesmakiem.

26 października, urodził się drugi syn, Wojtek – promiennie radosny od pierwszych chwil swojego życia. Gdy rzucam się w wir wszystkich spraw organizacyjnych, powoli wygasa we mnie poczucie winy, dezercji od ojcowskich powinności. Ale innego wyjścia nie mam. Trudno.

Dochodzimy jakoś do lodowca, na którym powinna gdzieś być baza pod Dhaulagiri, a w niej moi kumple. Tylko że lodowiec ma szerokość trzech, a może nawet i czterech kilometrów, wypatrzenie wśród nich namiotów okazuje się niezwykle trudne. Po pewnym czasie znajduję puszkę po konserwach. Polskich! Ten widok zamiast ucieszyć – wzbudza niepokój. Jeżeli puszki są, a bazy nie ma, oznacza to, że mogli już skończyć walkę z górą. Kręcę się coraz bardziej bezradnie po tym lodowym pustkowiu. Akurat wtedy widzę wyłaniające się w oddali zza załomu dwie sylwetki. Rozpoznaję z daleka, że to Janusz Skorek i Andrzej Czok. Nie wiem, skąd we mnie ta ochota do żartów i to właśnie w chwilę po nastroju, w którym przeważało przygnębienie ale... nie krzyczę, nie wymachuję wesoło ręką, nie skaczę z radości, tylko siadam w śniegu i czekam. Dopiero, gdy zbliżyli się do mnie na dwa metry, podrywam się z okrzykiem:

– Pasowa kontrola! Przepustku maté?

Ta nagła, niespotykana w himalajskiej scenerii, sytuacja przedrzeźniania stróżów zza bratniej granicy w Tatrach powoduje, że stają w miejscu jak wryci. Są zaskoczeni, niemal w szoku.

Baza znajdowała się zaledwie o... 20 metrów dalej. Mogłem jej jednak nigdy nie odnaleźć, bo jest jakby wciśnięta pod wielki, 20-metrowy kamień.

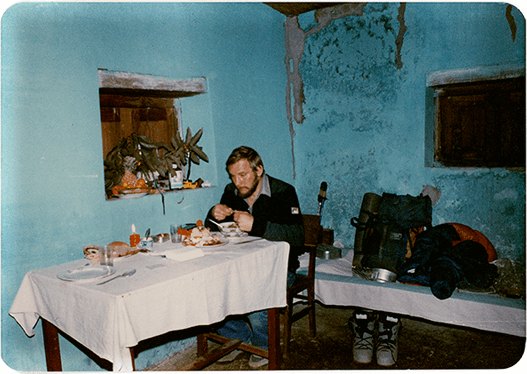

Pokhara, po stolicy, jest drugim co do wielkości miastem Nepalu. Tutaj przyszło mi spędzić Wigilię. Kupuję trochę południowych owoców, otwieram puszkę sardynek, gotuję barszcz z torebki zamiast tradycyjnej w moim domu zupy z suszonych śliwek.

Przywiozłem ze sobą opłatek, którym nie mam się z kim podzielić. Mam też Stary i Nowy Testament. Kiedy zapalam świeczkę, robi mi się przykro. Moja pierwsza, od niepamiętnych czasów, Wigilia spędzona poza domem. Piję łyk miejscowej gorzałki, która nie jest w stanie przezwyciężyć smutku. Co tu ukrywać, jestem bardzo bliski płaczu.

Następnego dnia był sylwester, którego przeznaczyłem na odpoczynek. Tutaj, o tej porze roku, w nocy jest zimno, więc „bal” trwał tylko dwie godziny, które upłynęły pod znakiem wspomnień. Ja też się trochę rozkleiłem, wspominając swoje sylwestry w Istebnej, gdzie tradycyjnie witałem każdy Nowy Rok. Robiliśmy kuligi, wypuszczaliśmy w niebo rakiety, Nowy Rok witaliśmy o północy zawsze na zewnątrz chaty.

Drugiego stycznia wyruszamy w górę. Idę z Andrzejem Czokiem i Januszem Skorkiem. Boję się trochę o moją aklimatyzację. Na razie jednak czuję się dobrze, nie odstaję od nich. Do obozu drugiego, trudnego do odnalezienia, bo zasypanego dokładnie śniegiem, dochodzimy około północy.

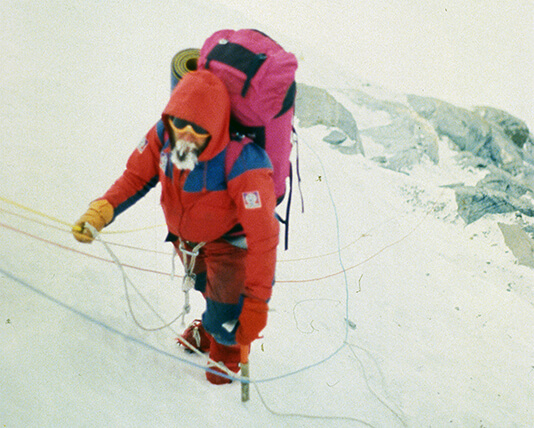

Wreszcie zakładamy obóz III, schodzimy i od tej pory rozwija się już akcja na serio. Jestem cały czas w szpicy, zakładamy obóz IV na wysokości 7000 m. Mamy świadomość, że jest to trochę nisko, ale początkowo jesteśmy dobrej myśli i chcemy z tej wysokości atakować szczyt.

Kolej na nas. Wychodzę z dwójki z Andrzejem i Mirkiem Kurasiem. W tym czasie obóz trzeci zostaje kompletnie zasypany. Nie ma go. Dochodzimy do obozu IV, który jest, jak na razie, najwyższy. Rano ubieramy się, czeka nas dzisiaj niełatwe zadanie – chcemy przecież ten namiot przenieść wyżej. W momencie, gdy jestem już właściwie gotowy, mam wyczołgiwać się z namiotu, czuję, że coś mnie nieustępliwie odpycha od jego ścianki. Zaczyna nas przytłaczać jakiś niewidzialny ciężar.

Pod koniec dnia dochodzimy na wysokość 7700 metrów, gdzie na małej grańce rozbijamy nasz pokiereszowany namiot, w którym przygotowujemy się do czekającej nas w następnym dniu wspinaczki. Jednak kłopoty bynajmniej się nie skończyły. Andrzej dopiero teraz przyznaje, że z jego nogami dzieje się coś złego. W ochraniaczach, gdy zaskoczyła go lawina, zepsuł się zamek, więc skazany był na zasznurowanie ich, co nie zabezpieczało w pełni już stóp. Nie mówi nic, odwraca się do mnie plecami i stara się jakoś te zgrubiałe stopy ocieplić. Masuje je wytrwale, po chwili pomrukuje z wyczuwalnym zadowoleniem, bo zaczyna stopniowo odzyskiwać czucie.