Wojtek i ja wyruszamy z twardym postanowieniem, że działamy w starym, żelaznym składzie. We dwójkę. Okazuje się, że w tym terminie, w to samo miejsce organizuje małą wyprawę Janusz Majer z Katowic. Jadą w czwórkę na Broad Peak. Łączymy więc siły, bo łączenie przygotowań do wyjazdu zawsze sprawę ułatwia. Ale w przygotowaniach wyprawy w naszych warunkach nie ma spraw łatwych. Zwłaszcza gdy w kraju brakuje wszystkiego, a najbardziej mięsa. Utkwiła mi w pamięci scena, która miała miejsce w pewnym Wysokim Urzędzie, od którego zależy zezwolenie na dodatkowy zakup mięsa. Po długich walkach u drzwi dostałem się przed oblicze samego Dyrektora, który – rozpostarty za biurkiem – ze słabo skrywaną niechęcią, powitał mnie słowami:

– No! Najwyższy już czas z tym skończyć. Ja, wiecie, jak wyjeżdżam na wycieczkę w góry, to przez cały rok oszczędzam sobie kartki i potem kupuję konserwy. A wy tu chcecie jakieś specjalne przydziały!

Jadę na luzie, niemal środkiem wąskiego pasa asfaltu, czuję, że wóz jest trochę przeładowany, ale to nie odgrywa takiej roli jak tam, na serpentynach. Czasem tylko drogę przecinają przepływy, jakby malutkie wiadukty, nad którymi chwilowo jest wąsko. Wjeżdżamy akurat na jeden z nich i decyduję się odbić trochę w prawo (w Pakistanie obowiązuje ruch lewostronny), żeby zjechać bardziej na środek. Robię to od niechcenia, rutynowo. I nagle włos mi się jeży na głowie. Samochód nie reaguje. Trwa to wszystko ułamki sekund, na drugi ruch nie mam już czasu. Jednym kołem wpadam na murek ograniczający przepust, wybija mi kierownicę z rąk. Nie mogę zrobić absolutnie nic. Wpadamy do rowu...

Nasze graty wyruszają ciężarowym mercedesem, którego właściciele, Rysiek Warecki i Tomek Świątkowski, za kilka dolarów dziennej diety i szansę zobaczenia lodowca Baltoro, podejmują się transportu naszych bagaży tak daleko, jak tylko się da. Wszystko działa jak w zegarku.

Z Islamabadu wyjeżdżamy o czwartej po południu, jedziemy całą noc. Z jednej strony zbocze, z drugiej przepaść, w której jakieś 200 metrów niżej wije się rzeka. „Karakorum Highway” mówią o tej trasie, ale my, tkwiąc za kółkiem, nie mieliśmy głowy do żartów. I nagle: Stop! Droga zamknięta. Naszą wykopaną w zboczu „autostradą” przeszła lawina kamieni i teraz je usuwają. Jest zatkana. Może to potrwać jeszcze cztery dni. Skręcam kierownicę do oporu, zawracam wóz i ruszam w kierunku najbliższego miasteczka, oddalonego o 40 mil Gilgitu.

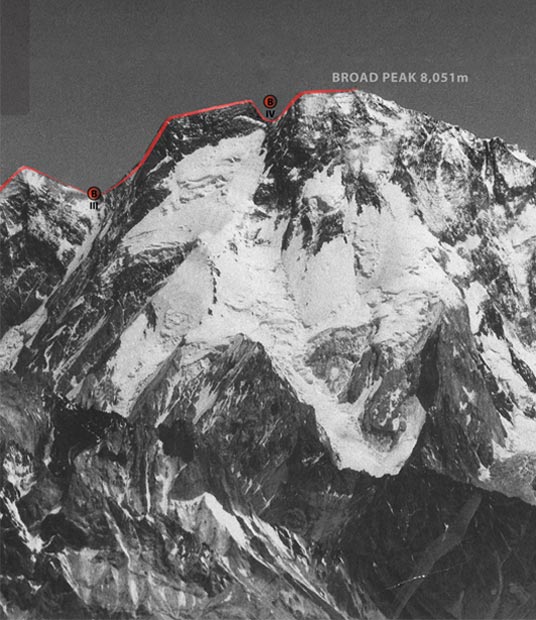

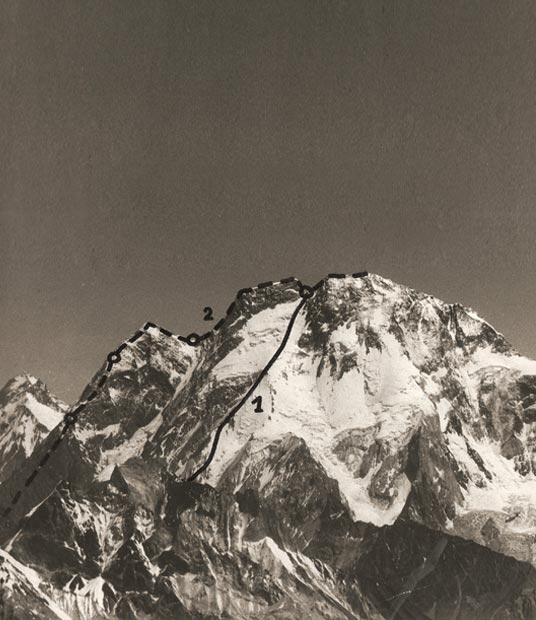

Bazę zakładamy pod południową granią Broad Peaku. Nie interesuje nas samo wejście na Broad Peak, na którym już byliśmy, chociaż „po cichu”, ale chcemy zrobić trawers wszystkich wierzchołków tej góry. Zacząć od południowej – dziewiczej jeszcze grani. Broad Peak jest górą, na której nie ma innej drogi prócz drogi pierwszych zdobywców. Rozpoczęcie trawersu granią południową pociągało nas najbardziej. Dlatego tutaj ustawiliśmy namioty, żeby być blisko i móc dobrze sprawdzić szanse dojścia i pokonania jej. Bo z daleka wszystko wygląda zachęcająco, ale nieczytelnie. Dolinka, grańka, ścianka, przełączka itd. Więc czas najwyższy zobaczyć, jak to wygląda naprawdę. Z bliska.

Już pierwszy rekonesans zamienia się w kubeł zimnej wody, wylany na nasze rozpalone głowy. Od samego początku musimy poręczować. wspinać się ze sztywną asekuracją. Przy kolejnym wyjściu decydujemy się na biwak w stromym polu lodowym. coś zaczyna bębnić w płótno namiotu. Po chwili czujemy, że ,,groch” leci coraz grubszy. A później następują już tylko dwa głuche łupnięcia. I nagle odkrywamy, że nad głowami mamy gwiazdy. Cały namiot jest rozerwany, a na środku, tam gdzie jeszcze parę minut temu siedziałem w kucki i gotowałem, leżą dwa kamole wielkości ludzkiej głowy.

Poszliśmy. Zabrało nam to wszystko pięć dni. Północny Wierzchołek nie poddawał się łatwo, czekała nas tam trudna wspinaczka (7100- 7538 - 7300 ). Wejście na Wierzchołek Środkowy było już łatwiejsze, w efekcie cały plan zrealizowaliśmy bez większych problemów i wynikających często z nich ,,poślizgów” (8016 -7800). [Następnie, 17 lipca, zdobyty został główny wierzchołek Broad Peaka- przyp. red.] (8047) Byliśmy znakomicie zaaklimatyzowani dzięki tym wcześniejszym rekonesansom na grani południowej. Wojtek miał rację, trawers od strony północnej był łatwiejszy. Ale jakże piękny mógł być, gdybyśmy zaczęli od południa?

Lód jest tak twardy, że nawet w rakach trudno się na nim utrzymać. Na ten widok siada nam „psycha”. W pewnym momencie Wojtek mówi:

-Jak na początek trawersu, jest trochę za trudno. Zacznijmy od ściany północnej. Przecież trawers jest ważniejszym celem niż sama droga.

Kiedy to mówi, czuję, że wyraźnie traci przekonanie do naszego pierwotnego planu. Byłem trochę innego zdania, ale mówiłem mało. W końcu bardzo niechętnie wydusiłem z siebie:

-Jeżeli jesteśmy już na siebie skazani, to niech ci będzie! Pójdziemy od strony północnej.